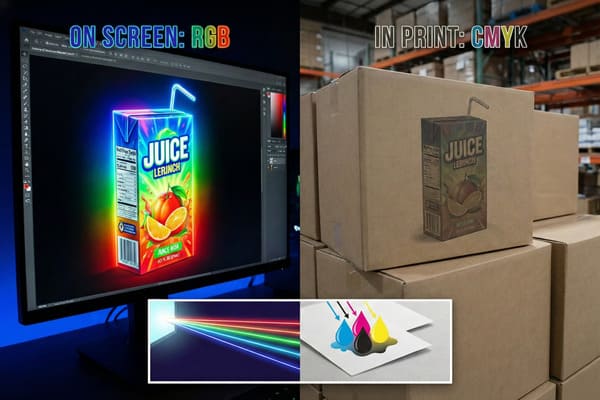

Designing your brand's packaging on a shiny 5K Retina display is satisfying, but opening the shipping container to find dull, muddy colors is a nightmare.

RGB (Red, Green, Blue) is not ideal for printing and packaging because it utilizes an additive light model, whereas printing requires the subtractive CMYK (Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, Key) ink process. This physics mismatch compresses the color gamut, causing vibrant on-screen tones to appear dull or muddy on physical substrates.

So, why does your monitor lie to you? And more importantly, how do we fix it before mass production starts?

Why is RGB not used for printing?

Sending an RGB file to a printing press is a bit like trying to pay for groceries with Monopoly money—the value just doesn't translate.

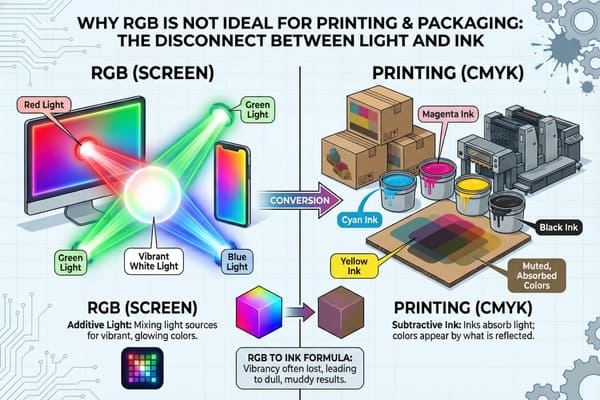

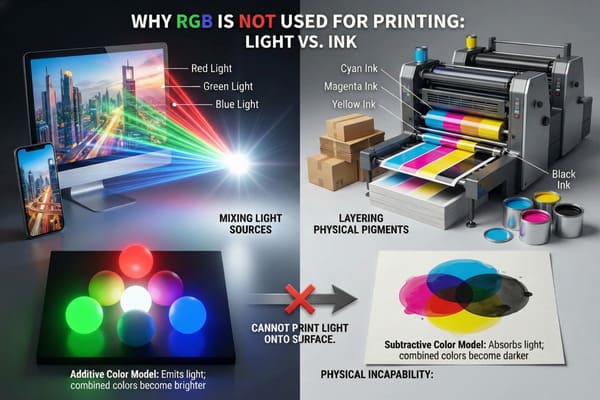

RGB is not used for printing because commercial presses utilize physical CMYK (Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, Key) inks that absorb light, whereas RGB devices emit light. This fundamental physics difference creates a gamut mismatch, where the broad spectrum of digital colors must be compressed into a narrower, duller printable range.

The Physics of Light Emission vs. Ink Absorption

It drove me crazy in the early days. I remember a client from New York who sent us a file with a neon "Electric Blue" background for a cosmetics display. On his screen, it looked glowing and futuristic. But when we ran it on our Heidelberg Speedmaster offset press, it came out looking like a bruised navy blue. He was furious, but physics is physics. You simply cannot print "light." This happens because monitors use an Additive Color Model1, starting with a black screen and blasting Red, Green, and Blue light at your eyes to create white. The more light you add, the brighter it gets. But printing on cardboard is a Subtractive Color Model2. We start with white paper—usually Clay Coated News Back (CCNB) or Virgin Kraft—and layer Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, and Black inks on top. These inks subtract (absorb) light bouncing off the paper rather than emitting it.

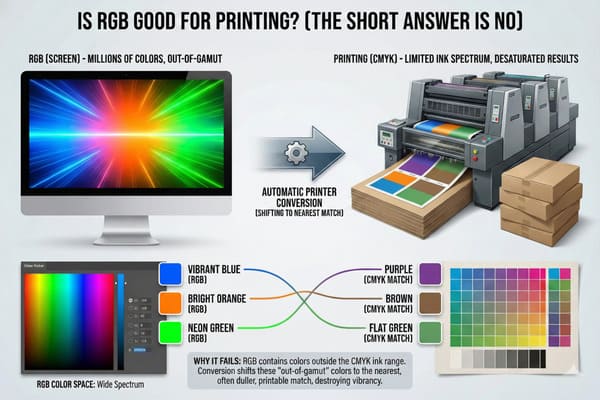

This physics mismatch creates the infamous "Muddy Color3" disappointment. The RGB gamut (the range of possible colors) is massive and contains millions of colors, including those super-bright neons. The CMYK gamut is significantly smaller. When your RGB file hits our RIP (Raster Image Processing) software, the software is forced to "clip" those out-of-gamut colors to the nearest printable match. Usually, that match is duller and darker because we cannot mix physical pigments to match the intensity of a light bulb. Furthermore, we have to consider the substrate itself. If we are printing on standard 32 ECT (Edge Crush Test) corrugated board, the paper acts like a sponge. It absorbs the ink dots, causing "Dot Gain4." An RGB file converted to CMYK often results in heavy ink coverage, which spreads on the porous paper fibers, making the image look even darker and muddier than intended. If you design in RGB, you are designing for a backlit world that simply doesn't exist on the factory floor.

| Feature | RGB (Red, Green, Blue) | CMYK (Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, Key) |

|---|---|---|

| Physics | Additive (Emits Light) | Subtractive (Reflects Light) |

| Base Canvas | Black Screen | White Paper/Board |

| Color Gamut | Wide (16+ Million Colors) | Narrow (Thousands of Colors) |

| Primary Use | Monitors, Cameras, Web | Offset Printing, Digital Printing |

| Neon Ability | Excellent | Impossible (without special Spot Inks) |

To stop you from panicking when the colors shift, we use GMG Color Proofing systems. I don't trust a screen. I trust the physical proof on the actual paper stock.

Is RGB good for printing?

Short answer: No. Long answer: It is a recipe for a "bait and switch" feeling that hurts your brand equity and creates structural risks.

RGB is not good for printing because it generates a false visual expectation that physical pigments cannot replicate on porous substrates. While RGB works perfectly for digital displays, using it for packaging results in unpredictable color shifts, muddy tones, and saturation loss during the mandatory conversion process.

The "Screen vs. Reality" Disappointment Gap

I treat your 100-unit trial like a 10,000-unit rollout, but that gets tricky if the source file is RGB. The biggest issue isn't just that the colors change; it's that they change unpredictably and can actually damage the cardboard structure. When a designer works in RGB, they often use "Rich Black" (R=0, G=0, B=0) for text or backgrounds without realizing it. When that converts to print, it doesn't just become K=100 (Black ink). It often converts to a heavy mix of all four inks (e.g., C=75, M=68, Y=67, K=90). This puts a massive load of wet ink onto the cardboard surface—sometimes exceeding 300% coverage.

Here is the messy reality of the shop floor: Cardboard is basically paper glue and air. If you dump that much liquid ink onto a B-flute sheet to try and match the depth of an RGB screen, the paper swells and loses rigidity. This leads to "Litho-Cracking5". I've seen it happen: we fold the display, and the printed surface cracks along the fold lines because the fibers are saturated and weak. I've had to scrap entire pallets of displays because the heavy ink coverage caused the liner to peel off in a humid warehouse. Additionally, you have to worry about the Washboard Effect6. Corrugated board has waves (flutes) inside. If we are printing a high-fidelity image converted from RGB, the slight desaturation combined with the wavy surface of standard B-flute makes the image look low-quality and textured. For my clients who demand perfection, like high-end tech brands, we switch to E-Flute7 (Micro-Flute) or Litho-Lam to minimize this texture. But if the color file is bad to begin with, no amount of smooth paper will fix the muddy tones. You are fighting a losing battle against the material itself.

| RGB Color Input | Likely CMYK Print Output | Why? |

|---|---|---|

| Neon Green | Forest Green | CMYK lacks the fluorescence of light. |

| Bright Orange | Burnt Sienna | Orange is notoriously hard to mix with C+M+Y. |

| Deep Blue | Purple-ish Blue | Cyan ink often leans towards blue-green. |

| Electric Violet | Muddy Purple | Out of gamut; requires a Pantone Violet to fix. |

My process involves using a Spectrophotometer to check the Delta-E. If your RGB file converts to a color that is more than 2.0 Delta-E away from your brand standard, we stop the press.

Why use CMYK in printing instead of RGB?

Retail giants like Walmart and Costco don't care what your design looks like on an iPad; they care about what it looks like under the fluorescent lights of their store aisles.

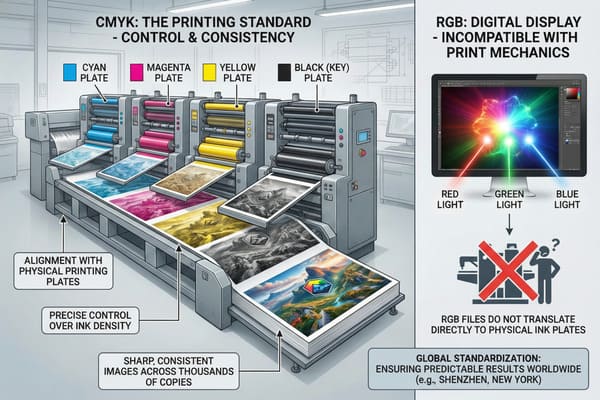

CMYK is used in printing instead of RGB because it aligns with the standardized four-color separation process required for industrial offset machinery. This subtractive color model allows manufacturers to control ink density precisely, ensuring that the approved physical proof matches the final production run within strict tolerances.

Standardization and Global Brand Consistency

In the factory, we don't paint; we separate. When we make printing plates for a run, we create four separate aluminum plates: one for Cyan, one for Magenta, one for Yellow, and one for Black. This is the global standard for offset lithography. Using CMYK8 gives us precise control over the final output. If I am printing a display for a hunting crossbow brand (like yours, David), and the "Camo Green" looks too yellow on the first sheet, I can physically adjust the ink keys on the Roland 900 press to reduce the Yellow density by 5%. If you sent me an RGB file, I am just guessing at the conversion because the data doesn't map directly to my ink keys. With CMYK, we speak the same language. We can tweak the flow of each specific color channel to correct issues on the fly without guessing.

We also strictly adhere to G7 Master Color Calibration9. This is a critical US standard that ensures our grayscale and color balance match what you see on a calibrated proof, specifically using GRACoL profiles10. Many Chinese factories use Japanese standards which tend to print darker and heavier, causing issues for US buyers. By sticking to CMYK and G7, I ensure that the red on your packaging box matches the red on your floor display, even if they were printed weeks apart. But sometimes, even CMYK isn't enough. For brand-critical colors (like Coca-Cola Red or Home Depot Orange), we don't mix CMYK at all. We use a Spot Color11 (Pantone/PMS). This is a pre-mixed bucket of ink that we pour into a fifth station on the press. It guarantees a perfect match every time. But to use Spot Colors effectively, your artwork still needs to be set up for print separation, not screen viewing.

| Capability | RGB Workflow | CMYK + Spot Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Ink Control | None (Automated conversion) | Precise (Manual adjustments on press) |

| Consistency | Low (Varies by device) | High (Standardized values) |

| Global Matching | Difficult | Easy (using ISO/G7 standards) |

| Cost | Low (Digital only) | Higher setup (Plates), lower unit cost |

We utilize a "Golden Sample" system. Once we get the CMYK color right on the first run, I sign that unit. It sits on the line, and every 100th box is compared to it.

What are the limitations of RGB?

It is not just about the color looking wrong; it is about the file technically breaking my production line and causing rejection at the retailer.

The limitations of RGB involve its inability to define specific separation data for physical ink plates, such as spot varnishes or metallic finishes. RGB files lack the necessary overprint attributes, leading to registration errors, fuzzy text, and white gaps on the final packaging edges during the die-cutting phase.

Beyond Color: The Technical Pre-Press Bottlenecks

Here is a headache I deal with weekly: Small text legibility. In RGB, black text is just "Black" (R0 G0 B0). But when converted to CMYK, that black text often becomes a "Rich Black" made of 4 dots (Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, and Black). If the printing press vibrates even slightly—we are talking 0.004 inches (0.1mm)—those four dots don't line up perfectly. This is called "Registration Drift12". The result is that your small instruction text looks fuzzy and has colored "halos" around it, making it unreadable for older shoppers. If you had designed in CMYK, you would have set that text to 100% K (Black only), which uses a single plate and stays crisp no matter what.

Then there is the issue of special finishes. You can't design "Gold" or "Silver" in RGB. I've had designers send me a file with a gradient yellow and gray, thinking it will print as metallic gold. It doesn't. It prints as yellow and gray mud. To get real silver, we need a separate channel for Pantone 877C13. An RGB file simply doesn't have the data structure to tell the machine "Put the shiny ink here," so the RIP software ignores it. Furthermore, we face the "Overprint" vs. "Knockout" issue. In vector software like Illustrator, if you don't set your cut lines to "Overprint," the artwork underneath gets deleted (knocked out). If the die-cutter shifts a fraction of a millimeter, you get an ugly white line on the edge of your product. RGB files often flatten these layers, making it impossible for my pre-press team to fix these trapping issues without rebuilding your entire art file from scratch, which delays your launch by days.

| Technical Issue | Cause in RGB | Result on Shelf |

|---|---|---|

| Fuzzy Text14 | 4-color black conversion | Unreadable instructions; poor user experience. |

| No Metallic | Lack of Spot Channels | "Gold" looks like dirty yellow. |

| White Gaps | Flattened layers/No trapping | Ugly white hairlines on edges. |

| File Errors | RIP software confusion | Production delays; missed launch dates. |

I provide a Standardized Dieline Template before you start. It sets the ground rules so your designer doesn't paint themselves into a corner.

Conclusion

The gap between a beautiful screen design and a physical cardboard display is where budgets are lost. You need a partner who understands both the physics of ink and the demands of US retail.

If you are worried about your current artwork or just want to see how your design translates to real life, I can help. Would you like to get a Free Structural 3D Rendering or perhaps a Physical White Sample sent to your office to test the fit before we commit to printing?

Understanding the Additive Color Model is crucial for grasping how colors are created on screens versus printed materials. ↩

Exploring the Subtractive Color Model will help you understand the limitations of color reproduction in print compared to digital displays. ↩

Learn about the causes of Muddy Color to avoid common pitfalls in design and ensure vibrant print results. ↩

Discover how Dot Gain impacts print quality and color accuracy, essential knowledge for any designer working with print media. ↩

Understanding Litho-Cracking can help you avoid costly printing mistakes and ensure high-quality results. ↩

Learn about the Washboard Effect to improve your printing techniques and achieve better visual quality. ↩

Discover the benefits of E-Flute for high-quality prints and how it can enhance your packaging solutions. ↩

Discovering the significance of CMYK in printing will provide insights into color management and the importance of color accuracy in your projects. ↩

Understanding G7 Master Color Calibration is essential for achieving consistent color quality in printing, ensuring your brand colors are accurately represented. ↩

Exploring GRACoL profiles will help you understand how to achieve optimal color reproduction in your print projects, crucial for brand consistency. ↩

Learning about Spot Color can enhance your printing knowledge, especially for achieving precise brand colors that stand out in the market. ↩

Understanding Registration Drift is crucial for ensuring print quality and avoiding costly errors in your projects. ↩

Learn how to effectively use Pantone 877C to achieve stunning metallic finishes in your designs. ↩

Discover techniques to prevent Fuzzy Text, ensuring your printed materials are clear and professional. ↩